Tags

apologetics, Atheism, Christianity, genocide, law, Locke, morality, philosophy, rights, scripture

Like all law students I took a course on “property.” Throughout my life, I was lucky enough to take courses from some very interesting people. My property professor, Douglas Kmiec,[1] was no exception.

The idea that we gain rights over what we create was to some extent developed by John Locke. He described how people will mix their labor with items from the common property and make it theirs.

“The labour of his body, and the work of his hands, we may say, are properly his. Whatsoever then he removes out of the state that nature hath provided, and left it in, he hath mixed his labour with, and joined to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his property. It being by him removed from the common state nature hath placed it in, it hath by this labour something annexed to it, that excludes the common right of other men: for this labour being the unquestionable property of the labourer, no man but he can have a right to what that is once joined to….”

John Locke Second Treatise of Civil Government Chapter 5.

I read this in my property class taught by Kmiec. He explained that I might pick up a branch in the forest. Now if I put it down again, then anyone else can pick it up and do what they want with it. But if I pick it up and carve it into a wooden statue, well then it’s mine. At that point I would have the right to do with it what I wanted even destroy it, but no one else would have that right. I thought it was an interesting insight.

Ok so now many atheists want to say God is a “murderer!” He asked/commanded people to kill others. We have such stories in the Old Testament. How can we worship such a God?

Well first of all I tend not to believe the Old Testament is literal. I think the Old Testament is by and large a collection of stories. Yes the Holy Spirit inspired them but how exactly that works, I do not pretend to speak for that Holy Spirit. But even an atheist should consider that Jewish scripture consists of what possibly the very best and brightest cultures thought was some of their best literature. I agree some books do nothing for me but other books I find delightful and wonderful. I am somewhat saddened when I see people reading it only for the purpose they want to get out of it instead of thinking about what the author was up to.

Now although I do not take the Old Testament literally I do think it teaches true messages. But what message can Abraham being commanded to kill his son possibly be teaching? What can stories about God wiping out whole cities be teaching? One answer is that it teaches God is our creator and as such he is not like us. We are not the same. Regardless of what we or even God might want the truth is we are not the same. Reality doesn’t cater to our wants.

Let’s think about this. If a lion intentionally kills a human without justification we don’t say that it is a “murderer.” If a human intentionally kills a human without justification he/she is a murderer. What if God intentionally kills humans? Should God be treated like other humans? This is the hidden assumption of every anti-theist blog crying out that God is a murderer. I just read a paper which seems to imply God committed a holocaust against children who died from natural causes. I am not suggesting that God is not a murderer for the same reasons a lion is not a murder. But I am saying we should not automatically assume God is just like us, in this analysis.

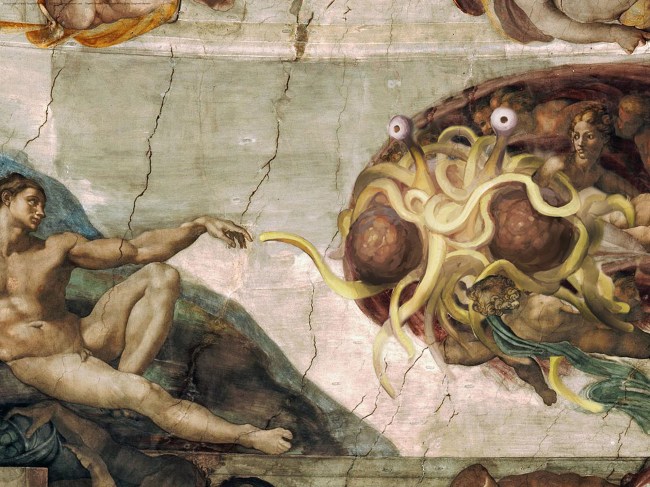

Here is something to consider. If I create a sand castle, I can destroy it and it is not immoral. If someone else destroys my sand castle it is wrong, unless I as the creator give them permission. God created us and he can destroy us and it is not immoral. Others however cannot destroy us and remain blameless, unless they are given permission by our creator.

I realize that this is not an appealing view. But if God is bound by the rules of Logic not even he can change that fact can he? If we are in fact, created by God we cannot truthfully claim otherwise. Even God cannot make this truth, false. This wounds our pride and tradition teaches it wounded Satan’s pride as well. He was unhappy with the truth that he was not like God, and rebelled against it.

“How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning! how art thou cut down to the ground, which didst weaken the nations! For thou hast said in thine heart, I will ascend into heaven, I will exalt my throne above the stars of God: I will sit also upon the mount of the congregation, in the sides of the north: I will ascend above the heights of the clouds; I will be like the most High. Yet thou shalt be brought down to hell, to the sides of the pit.” Isaiah 14:12-14[2]

Now my point is not to say the people who claim God is a murderer are “Satans.” Not at all. But it is to say that they are not accounting for the fact that Christians believe God is our creator and generally we think a creator has a right to destroy his creations. They engage in special pleading when they refuse to acknowledge this principle when discussing God’s relationship to us. This is a double standard. They recognize a painter has a right to destroy his painting if he is unhappy with it, but they want to deny this right to a creator God.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Before I did my blog arguing that marriage should no longer be governed by the state I googled to see if anyone else came to the same conclusion. I was somewhat surprised to see my old Property and Constitutional Law Professor arguing the same thing. Doug Kmiec is an inspirational professor who brought energy and excitement to everything he taught. I am not surprised by this quote from Wikipedia:

“On July 2, 2009, President Obama nominated Kmiec as Ambassador to Malta.[24] He was confirmed by the Senate. In April 2011, he was criticized by the Inspector General of the State Department for spending too much time on what the OIG reported as unofficial (religious) duties, which Kmiec saw as integral to his ambassadorial role.”

And I likewise am not at all surprised by this quote from Tiffany Stanley of The New Republic:

“in the annals of diplomatic misbehavior, Kmiec’s is rather an unusual case. Even the critical OIG report notes that embassy morale was good, he was respected by the Maltese and his staff, and had ‘achieved some policy successes’. The problem, it seems, was that Kmiec may have taken the job a little too seriously.”[27] Columnist Tim Rutten of the Los Angeles Times writes: “Over the last few years, Kmiec has emerged as one of this country’s most important witnesses to the proposition that religious conviction and political civility need not be at odds; that reasonable people of determined good conscience, whatever their faith or lack thereof, can find ways to cooperate in the common good. Though Kmiec has not sought their intervention, the president and the secretary of State ought to deal with the bureaucrats seeking to silence a voice whose only offense is to speak in the vocabulary of our own better angels.”

I read some other things that make me believe he likely had some hard times. I wish Doug Kmiec the best, and will keep him in my prayers.

[2] But see: https://bible.org/article/lucifer-devil-isaiah-1412-kjv-argument-against-modern-translations and http://pastordougroman.wordpress.com/2009/11/17/do-isaiah-14-and-ezekiel-28-refer-to-satan/